It is likely that the name Coxhoe was taken from the person that originally owned the area. It is not known when the villages of Coxhoe and Quarrington Hill were first established. There is evidence that the name “Coxhoe” has changed over time. For example, in 1235 it was known as Cokeshoui, in 1344 Coksouw, in 1553 Coksow and 1794 Coxsey. The word “hoe” is an Old English word for promontory.

The modern village of Coxhoe developed during the 18th and 19th centuries, spurred by coal mining, first recorded in 1750. Coxhoe Colliery was sunk in 1827; from 1801 to 1841 the population rose from 117 to 3904. Remains of other elements of the coal industry are still visible nearby. The buildings of Heugh Hall are now part of a farm, and the course of its wagon way is still visible as an earthwork.

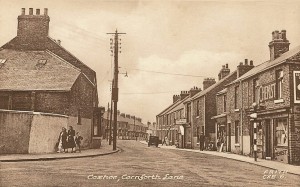

Coxhoe had two railway stations, one at the south end and one at the north. There was a pottery at Coxhoe from 1769 producing coarse brown pots, and from 1851 it also began to make clay tobacco pipes. Coxhoe also had its own gasworks, which produced gas from local coal; it was then sent around the village by a system of pipes. Most other coal was transported out of Coxhoe by the Clarence Railway.

Coxhoe Hall

Coxhoe Hall was a five-bay, 2½-story house of c.1725, built for John Burdon on the site of a Tudor house. This plain, classical residence was later given a Gothic trim, with battlements and pointed windows.

The earlier medieval house on the site belonged to the Blakiston Family from c.1400 to 1600, and afterwards to the Kennets and the Earls of Seaforth. The medieval manor house was later developed and the house – Coxhoe Hall – was formed as the birthplace of poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Rebuilt in 1725 in a Georgian Gothic style, it was considered to be one of the finest houses in County Durham. It was set high on a south facing hillside adjacent to the site of Coxhoe medieval village. A tree-lined avenue led to the Hall and it was surrounded by grounds with terraces, tennis courts and walled garden.

The house was bought by the East Hetton Colliery Company in 1938 and was used to house Italian and German prisoners-of-war in WW2. The hall was condemned as unsafe by the National Coal Board and demolished in 1956, leaving the ground plan and service yard still visible. Cellars are now filled with rubble and appear to contain much decorative plaster work from the demolished structure. The drive and gate posts still remain, as does a walled garden to the north-east.

Recent Comments